After the Children of Israel settled the land of Caanan, they eventually split into two Kingdoms, the north and south. The descendants of Judah were predominant among the peoples of the Southern Kingdom, which is why it was known as Judea and not Israel. Today, the nation of Israel, which are descendants of the people of Judea of New Testament times (the Jews), occupies the same land as the tribes of the Southern Kingdom and the people of Judea (Jews) of New Testament times.

The Northern Kingdom, from which they seceded, was ruled after the split by descendants of Ephraim, hence their kingdom was known as The House of Israel, he being the recipient of the birthright from Israel/Jacob. All references in The Bible to The House of Israel are therefore not references to the forefathers of today's Jews. Isaiah 11:10-16 is one of many Biblical references to Israel and Judah which confirm that the Israelites and the Jews/Judahites are two different peoples. When the Jews re-established the Jewish state of Israel in 1948, it should really have been called Judea, as it was in Jesus' time, as the right to use that name had not been bestowed upon them or their ancestors by Israel back in the Book of Genesis. The incorrect use of the name has brought great confusion and clouded the truth in the eyes of many Christians today about who the prophets were talking about when they referred to Israel.

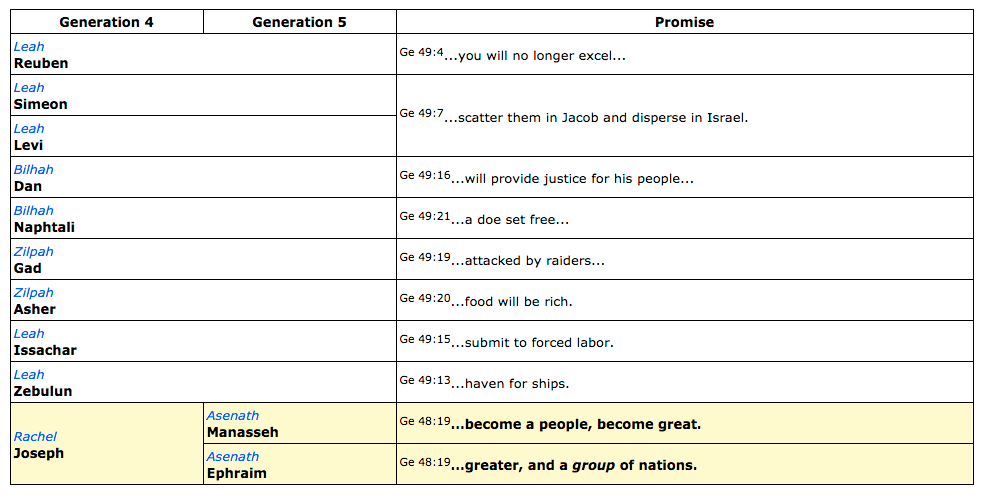

During the period of the Judges and the early kings (estimated at being around 1200 to 1000 BC), the Israelites, otherwise known as the Twelve Tribes of Israel, consisted of twelve tribes, which, according to the Book of Genesis, were named after the twelve sons of Jacob: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Joseph, and Benjamin. The term "children of Israel" is used to mean both the twelve sons of Jacob (whose name was changed to Israel) and collectively the twelve tribes. Joseph (the most famous of the twelve sons, he of the dreams and multi-coloured coat) did not actually have a tribe named after him; instead, his two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, each gave rise to tribes. That would make thirteen tribes, not twelve, but the tribe of Levi took on a priestly role (the only tribe to remain loyal to God and to Moses during the golden calf episode) without a specific region of settlement, and so is sometimes excluded from the count.

This patriarchal tribal pattern was characteristic of semi-nomadic peoples throughout the ancient Near East: the Arameans and Ishmaelites and Midianites and Edomites were also conglomerations of clans with inter-tribal alliances expressed in terms of brotherhood. Modern archaeologists and historians debate whether the Jacob actually had twelve sons, and if he did, if sons of Jacob did indeed give birth to the tribes, or whether the tribal alliances gave birth to the stories about common ancestry.

The Bible describes how the twelve tribes were enslaved in Egypt, escaped during the Exodus (around 1250 BC), and settled in the land of Canaan, each tribe occupying a separate territory (except the tribe of Levi.) Over the next two centuries, the strength of individual tribes waxed and waned. For example, early on the tribe of Simeon had clearly lost its importance as an independent tribe and was largely swallowed up by Judah (see Joshua 19:1 and 1 Chronicles 4:24-43).

The Bible describes how the tribes were then united under King David (around 1000 BC), who set the capital in Jerusalem (an area under the control of the tribe of Judah). David's son, Solomon, built the first Temple. Following the death of Solomon and after the civil war in the time of Solomon's son Rehoboam, said to have been around 931 BC, ten tribes split off the United Monarchy to create the northern kingdom of Israel. I Kings 12 describes the split arising on account of taxes, but there were also undoubtedly deep-rooted tensions between the northern and southern tribes, which had not been obliterated even after nearly a century of a united kingdom. So the Israelites were divided into two kingdoms:

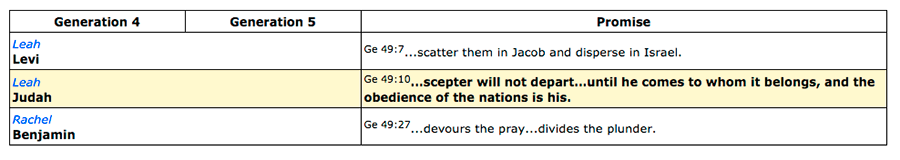

The Southern Kingdom's Patriarchs and Promises- South: the Kingdom or House of Judah with Jerusalem as its capital, consisting of the territory of the tribes of Judah, the remants of Simeon and (most of) Benjamin. Much of the priestly tribe of Levi, affiliated with the Temple, also lived in the southern kingdom.

- North: the Kingdom or House of Israel. These were the nine landed tribes Zebulun, Issachar, Asher, Naphtali, Dan, Manasseh, Ephraim, Reuben and Gad, and some of Levi which had no land allocation. The Bible makes no reference at this point to the Tribe of Simeon, and some believe that the tribe had already disappeared due to the curse of Jacob. They were dominated by the tribe of Ephraim, with Shechem as its capital. Half a century later, during the reign of king Omri, the northern kingdom adopted the name of its new capital, Samaria; in the Bible, the northern Kingdom is usually referred to as Israel. Traditionally, the northern kingdom was the Ten Tribes.

The northerners lost access to Jerusalem as the capital and so choose Tizrah and later Samaria as their capital. The southerners remained at Jerusalem. These two kingdoms held various promises made to Abraham. The promises matched the tribes that made up each nation. The following two tables take the previous promises table and split it along the same lines as the nation was split at the time of the civil war. The first chart is the same list of patriarchs and promises that landed in the northern kingdom, the second chart is the southern kingdom. Note that the Levites were spread proportionately throughout the kingdom, so it has a representative group in both nations.

An interesting thing has happened at this point. The two leading brothers Joseph and Judah are now leading separate kingdoms. The promises that each one holds also lands in these separate kingdoms. The other tribes, not having significant promises, are not really interesting in this story at this level. These two kingdoms went on to build separate and distinct histories. The Books of 1 and 2 Kings covers the history of the kings in both kingdoms. The Books of 1 and 2 Chronicles omits the Northern Kingdom and focuses exclusively on the southerners.

After the split, the two kingdoms spent a decade fighting a merciless war between themselves, not only over territory, but over religion (the southern kingdom insisted that religion was centralised in Jerusalem) and culture. However, that aside, the two Israelite kingdoms existed side by side for about two hundred years until the invaders came. In the year 722 BC, the Assyrians under Shalmaneser V and then under Sargon II conquered the northern Kingdom of Israel, destroyed its capital Samaria and sent the Israelites into exile and captivity in Khorason, now part of eastern Iran and western Afghanistan. The Ten Lost Tribes are those who were deported at that time. In Jewish popular culture, the ten tribes never returned to the Promised Land but disappeared from history, leaving only the tribes of Benjamin and Judah and the Levi who evolved into the modern day Jews.

The Assyrian invasion is one of the few events during the First Temple period that is documented by sources other than the Bible, and so provides a dating point as well as outside verification of the Biblical narrative. The story is recounted in II Kings 17 with considerable emotion, and is noted more drily in the annals of Sargon II, King of Assyria: "In the beginning of my royal rule, I have [besieged and conquered] the city of the Samarians . . . I lead away 27,290 of its inhabitants as captives and took some of them as soldiers for the fifty chariots of my royal regiments. I have rebuilt the city better than it had been before and settled it with people which I brought from the lands of my conquests. I have put an officer of mine as their lord, and imposed upon them a tribute as on other Assyrian subjects."

In 586 BCE the nation of Judah (the southern kingdom) was conquered by Babylon. About 50 years later, in 539 BCE, the Persians (who had recently conquered Babylon) allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. By the end of this era, members of the tribes seem to have abandoned their individual identities in favor of a common one.

Undoubtedly, a combination of social, political, and economic factors had led to the decline of the northern kingdom before its military conquest. Five royal dynasties rose and fell within half a century, a sure sign of social instability. Wealth was concentrated in the hands of a minority of landowners while the masses were pauperised. The prophet Amos, writing around 750 BC, predicted that social decadence would lead to national ruin and exile.

That's about as far as history and the Old Testament will take us. Now comes the speculation and historical data: what really happened to the ten tribes of the Northern Kingdom? To sum it up in one word, they became lost. There have been innumerable theories and legends over the centuries as to their fate. In those days, political conquest often meant national annihilation. The northern tribes ceased to exist as separate entities when they lost independence on their land. The ultimate fate of the exiles is, in fact, unknown. But there are three possibilities, all of which probably happened:

(A) Some went south, fleeing to the still-surviving southern kingdom of Judah, and remained part of the Jewish people. Richard Elliott Friedman, in his book Who Wrote the Bible?, suggests that these exiles from the northern kingdom would have assimilated into Judea, producing a re-united culture and religion, and editing the different Biblical strands into one common text. Studies of the first five books of the Bible by linguists confirm this - all five books appear to be compisite documents that were probably pieced together from two or possibly three earlier documents some time in the 3rd or 4th century before Christ. (B) Some stayed put. Those who remained in the northern territory were soon assimilated with the peoples that Sargon II brought to Samaria. Those who remained were mixed with other peoples brought in to the northern territory, to become the nucleus of a new people in the land of Israel, the Samaritans.

(C) Many were deported and lost their separate identity as Israelites. Assyrian policy was to obliterate national entities by population transfer. The New Testament writings confirm this is what happened. Numerous references are made to the dispersion in the New Testament, confirming that the identity and location of at least some of the dispersed was still known at that time.

The historical records of Sargon II, King of Assyria, documents the number of dispersed persons as 27,290. Judah in the south had been steadfast in its monotheism, but paganism had been prevalent and tolerated in the northern kingdom. Thus, after the conquest of 722 BC, the northern tribes had no cultural protection against assimilation.

Either way, within a generation or two following the Assyrian resettlement policy, the ten tribes had vanished, assimilated totally into the Assyrian empire. Note that, when the southern tribes of Judah were conquered by the Babylonians 150 years later, things were very different - they retained their identity, even in exile, largely on account of their religion. By the time of the birth of Jesus, their country was known as Judea and they were known as The Jews. Both names recall Judah, their main patriarch.

The Bible text says little about the fate of the northen kingdom's peoples, except that they were carried away and placed "in Halah and in Habor, on the river of Gozan in the cities of the Medes." These places have not been identified with any certainty. The Talmud presents contradictory opinions. One is that the ten tribes were assimilated and merged with the peoples among whom they lived; this is (as noted) by far the most likely explanation. The second Talmudic opinion holds that the northern exiles survived and joined the exiles from Judah (6th century BC) who returned to their homeland from Babylon in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah.

The prophet Ezekiel (about 580 BC) speaks of the ultimate reunion of the House of Israel and the House of Judah, which supports this interpretation. Non-Biblical historic records indicate that such a reunion did occur, but the number who returned in comparison to the number who had originally gone into exile left a large number of the latter unaccounted for. The writings of other Old Testament prophets unanimously support this and tell of a future time when the National of Israel will be restored both to God and to the Kingdom of Judah after God drawn these people out from 'the islands of the ends of the world' in which these people will eventually have settled.

In Matthew 10, Jesus told his disciples not to go to the Gentiles (not yet, anyway) or even to the Samaritans (they occupied the land of the former Northern Kingdom) but to go to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. In Matthew Mat 10:6 But go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. 15:24, Jesus said, " I am not sent but unto the lost sheep of the House of Israel." Luke 2:36 specifically identifies Anna as being "of the tribe of Asher", implying that at least a few people had maintained their tribal identity.

Some passages from the New Testament throw further light on the matter. For instance, the book of James starts out with a greeting "to the twelve tribes in the Dispersion," implying that his writings would reach those of the dispersed tribes, they being the 'lost sheep of the House of Israel' that Jesus had spoken about. The words of Jesus and the greeting of James both indicate that the people of that time knew who and where these people were, and that they had not yet become fully assimilated into other societies so as to have become 'lost', even though it was around 750 years after they had first been taken into captivity.

Prior to 722 BC, all Israelites could identify themselves from the tribes from which they descended. But from the Babylonian Exile on, all Jews are assumed to descend from only from one tribe, Judah, except for those who trace their ancestry to the priestly tribe of Levi or to the Kohanim (a subgroup of the tribe of Levi.) Therefore, from the persepctive of Jewish geneaology, the Ten Tribes are assumed to have vanished without a trace.

In one of the apocyphal books (rejected from inclusion in the canonical Bible), 2 Esdras 13:39-47 describes how the "nine tribes that were taken away from their own land into exile . . . formed this plan for themselves, that they would leave the multitude of nations and go to a more distant region, where no human beings had ever lived, so that there at least they might keep the statutes . . ." That reference may have been the fuel for the notion of the lost tribes living somewhere far from "civilisation."

Medieval Jewish writing is full of references to one or another of the lost tribes. Some travellers of the Middle Ages claimed to have visited among them, such as Eldad the Danite who claimed to have found them in North Africa, called the "sons of Moses," guarded by a river made impassable six days in the week by its stone-throwing, turbulent waters. Yemenite Jews, the Beni Israel of Afghanistan, and the Ethiopian Jews all claim to be descended from one or another of the lost tribes of the ancient Israelites. Various theories have tried to identify the Tatars, the Shindai class of Japan. Several decades ago, some scholars discovered striking similarities between the traditions of the Torah and of some North American Indian tribes (for example, an Autumn harvest holiday that involves building and living in huts), leading them to conjecture descent from the ten lost tribes. Many of these theories are purely speculative, and generally without historic (or Biblical) foundation, however none can be totally ruled out.

Design by W3layouts