'Trial' Shipwreck

It would not be surprising if there had been other unrecorded shipwrecks prior to that of the Trial off the Western Australian coast in 1622; for the Australian coast is from a navigator's point of view a most inhospitable and dangerous shore. Its northern flanks are guarded by treacherous reefs and shoals while its southern coasts are swept by fierce seasonal storms. The surface of its surrounding seas is often calm and tranquil, and always very deceptive.

In the year 1622 the Trial left London on an expedition to Java, with an eye to trade. Re-victualled and refreshed, she left the Cape of Good Hope on 19th March 1622; two months later she ran to her doom on a shelf of rock. Of her company of 143, 97 men were lost, the others made a most remarkable escape in two small boats. The letters written by Thomas Bright, who was fortunate enough to be in one of those boats, are still preserved in the India Office, London; and it is to them and the letters of John Brooke, master, that posterity owes this first authentic record of a shipwreck on the Australian coast.

Brooke wrote from Java, nearly three months after the wreck. The Trial, he said, had a good run across the Indian Ocean, and finally sighted land in 22 degrees of latitude, on 1st May, on her forty-second day of open sea voyaging. To the skipper the distant land appeared to be an island; but it has since been identified as Point Cloates, which is practically the most westerly point of the Australian mainland, just south of North-West Cape.

It was not Java: that much John Brooke knew; so the Trial stood to her course, the "island" dropping down to the south-east horizon. But north and north-east winds sprang up, and between 5th and 24th May the little ship made scarcely any headway. These circumstances were all in the life of a mariner in the days of sail, and when the wind veered to the south-east on 25th May, the Trial's luck had changed, she took a northeast tack.

The night of 25th May - like so many other nights of coastal tragedy around Australia's shores - was calm and clear. The setting sun dropped over the horizon, the sky was tranquil, the water almost still. There was no sign of land, no weed or mud stirred in the water, no creamy comb of spume to betray a reef or sunken rock. "Fayre weather and smoothe watter - the shipp strooke," wrote Brooke with dramatic simplicity, in his letter. On that perfect night, under a dark, star-studded sky, that the Trial ran without warning upon a point of rock and shuddered to a standstill. So contrary were the surrounding signs that even then some of those experienced sailors refused to believe the ship was in peril. But there was no doubting it.

"I ran to the Poope and hove the leads," Brooke wrote. "I found but three fadom watter, 60 men being upon deck, five of them would not believe that she had strooke, I cryinge to them to beare up and tacke to westward. They did ther beste, but the rocke being sharpe the ship was presentlie full of watter. For the most part these rocks lie two fadom under watter. It struck my men in such a mayze when I said the ship strooke wid they could see neyther breach, land, rocks, change of watter nor signe of danger. Thomas Bright observed that the "hold of the shipp was full of watter in an instant."

Meanwhile the wind freshened and the Trial swayed and struck the second time. Brooke hurried about his business, making every possible effort to save the ship. He sent out a skiff and put members of the crew to sounding about the vessel in the darkness to ascertain the exact condition of the water. They discovered that the ship had been caught on a sharp sunken rock half a cable in length, and was pierced astern. There was no surrounding shallow; these teeth of rock rose like the spires of a deathly cathedral from some much lower foundations; and there being no surrounding shallow, the task of the shipwrecked was made the harder. "I made all the waye I could to gett out my long boate, and by 2 of the clocke had gotten her out and hanged her in the tackles over the side," wrote Brooke. He then instructed Thomas Bright to supervise the handling of the long boat- "the hold of the shipp was full of watter in an instantx 128 soules left to God's mercye, whereof 36 were saved," Bright commented.

Keen as were both men in their powers of observation, they were swift to work. Bright had the long boat hanging in readiness for a little while before the men in the skiff reported, as a result of their examination, that there was no hope at all of saving the Trial. The wind was freshening minute by minute, which rendered it still more dangerous to cling to the wreck; and Brooke, "seeing the shipp full of watter and the wind to increase, made all the means I could to save as manie as I could. The long boat put off at 4 in the morning. Half an hour after the fore part of the boat fell to pieces."

Under Brooke's orders Bright lowered the long boat and took into it as many as it would safely accommodate 36, he estimated, was the maximum. Then he and his fortunate fellows pushed off from the wreck, feeling their way through the darkness and rowing slowly, lest the smaller vessel too should be cast onto some similar needle point of rock. "We stayed near the shipp until day," he wrote from Java later, "but the sea was running soe high that we durst not venture near."

At length, seeing the hopelessness of trying any movement at all for the benefit of those remaining on the wreck, Bright conceived it his duty to save as many as he could of the men in the long boat; so they began to row in earnest, watching the hulk of their ship grow smaller in the sea as they made their way in the general direction of Java. They were commencing, from the first recorded Australian wreck, the first of many notable long voyages performed in small boats- the first, but by no means the unhappiest, of those small boat voyages.

The long boat came to an island (since identified as Barrow Island) where the men went ashore in the hope of increasing their scanty supply of provisions. There was but one barrecoe of water and "a few victuals" in the long boat - not nearly enough for the voyage they hoped to make. And Barrow Island proved a barren island, with "no watter except what the good, Lord gave per rayne," and no birds, animals or vegetables which could be used for food. Nevertheless, after the long voyage- across the Indian Ocean, and the exciting escape from the wreck, the sailors were glad enough to feel land under their feet again, and spent seven days on the island. It was a small, rocky place from the pinnacles of which other low-lying islands could be seen.

Bright himself, although he was "alone on the wide wide sea", with very little prospect of ever reaching civilization again, and with every possibility of shortly starving to death, preserved remarkable calmness. He seems to have kept perfect discipline among the men, as well- which is equally a tribute to Bright and to the character of the men, as the records of sea-horror show all too clearly. Maybe, too, in those days before psychology was a science, Bright had a clear appreciation of the value of work; for he spent part of his time preparing "2 draughts" of the group of islands, mapping in other islands visible from the one on which he was, for the time being, marooned. He also wrote a description of the archipelago in which he stated that there were other islands everywhere.

While Bright and his men were thus safely ashore and calmly engaged, John Brooke was fighting out his own destiny; for he had realised the hopelessness of sticking to the ship any longer, and had prepared to make an attempt, in the small skiff, to reach Java. He also came across "a little, low island" - probably another of the archipelago Bright had struck- and he also remarked upon the barrenness of his discovery. He kept his course, however, and on 8th June sighted the east end of the island of Java, after a voyage of 14 days. The skiff was better equipped with provisions, having "one barrecoe of water, 2 cases of bottles, 2 runnets of aquavite, 40 li. bread."

For four days together there was continuous rain, so that the men in the skiff ran no danger at all of perishing from thirst. And having reached Java they pushed onward in their little boat, reaching Batavia on June 26, getting a good reception, and settling down to write a letter which, when delivered to the London office perhaps three months later, would tell the owners of the Trial that they had lost their vessel long ago. He was in no position in that letter, however, to give any assurances on Bright's behalf; for Bright and his long boat moved on from their desert island and they, too, arrived safely in Java 3 days later. They did not attempt to reach Batavia, so Bright's letter, written independently from Java, told the story of the 36 who were saved, making no reference to the good fortune of the captain and his nine companions. The fate of those who were left on the vessel may be imagined; it will never, mercifully, be described.

Already when Brooke left he had seen the fore part of the vessel tear away from the hull and crash into the sea; and that sea was already marked by flashing fins. The remainder of the ship could not have lasted long. The sweeping seas would batter it mercilessly, wrenching planks from their ribs, crumbling the sodden timbers under the feet of the wretched men for whom there was no hope. Hunger and thirst would begin to prey upon those men as they waited, helplessly, for the coming of death. Perhaps, when they were finally thrown into the sea, the swift attack of the shark, or the suf-focation of the waves, was relief from their last hours (or were they days?) upon the Trial.

No rescue vessels put back into that uncharted sea on the off-chance of finding the unknown rocks; and had they done so they would have been too late to rescue the men of the Trial. By the time Brooke reached Java every man left behind must have gone to his sailor's grave; and Brooke, who seems to have been blessed with a share of common sense as well as of humanity, did not try anything so crazy as sending living men after dead ones. However, when the story of the Trial became known in London, attempts were made to locate the rocks which had caused the wreck. Thomas Bright's charts, so calmly made between a dangerous past and an uncertain future, reached London safely, but were either too crude to be useful or were lost after their arrival.

There's an intriguing footnote to the story of the Trial. Brooke, its errant captain, was given the command of another East Indiaman, the Moone, on which he returned to England from Batavia. Off the coast of Dover, it was wrecked, apparently deliberately so. Brooke found himself in prison for the duration of the two-year court case, which the Company ultimately dropped. Brooke may have been free but he certainly wasn't exonerated.

Finding the wreck

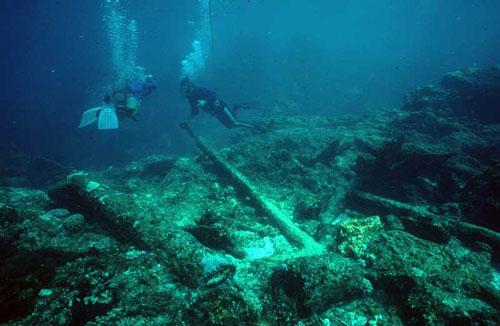

A wreck believed to be the Trial was encountered on the Trial Rocks, an isolated reef north of the Montebello group of islands, in 1969 by a group of skin-divers from Perth, their leader was Eric Christiansen and included Dr Naoom Haimson, Alan Robinson and Dave Nelly. Under the Maritime Act an ex gratia payment of $2,000 was sent to the group. The site is exposed to huge Indian Ocean swells and is a dangerous place to dive.The Western Australia Museum first investigated the wreck site in 1971. While there are half a dozen cannon and quite a few anchors beneath the waves, only about 20 artefacts have been recovered. Nothing has been raised that conclusively proves it is the Trial, although circumstantial evidence clearly suggests that it is.