1912: Building the Trans Australia Railway

In the closing years of the 19th century, the task of uniting Australia's six autonomous British settlements under one central (Federal) government was one that had herculean proportions. State rivalries seemed to impede the federation fathers at every step. Neither New South Wales nor Victoria wanted to see the other as the seat of Federal government and each was aware that the other colonies may well benefit, by form of a virtual subsidy, from their wealth and prosperity. Western Australia was a reluctant guest at the Federation table. She argued that the distance between her and the eastern sea-board would mean that the interests of her people would be ignored. WA believed she was neither a Cinderella state, nor poor cousin. The Kalgoorlie/Coolgardie goldfields gave hint of vast potential mineral wealth. In effect she would be milked for her economic contribution without having any political influence in a central government.

The Premier of Western Australia, (Sir) John Forrest, believed that a railway linking WA to the other states of Australia would help to unify the various Western Australian factions. In 1896, when the railway reached Kalgoorlie from Perth, Forrest promised the Goldfields residents that the railway would not stop at Kalgoorlie. This was a promise they did not let him forget. Thus the lure of a trans-continental railway did become the 'carrot' which led WA to join the Federation of Australia on 1st January 1901. Unfortunately it was only a promise and not a cast iron guarantee. This resulted in many years of lobbying by Western Australia to see it come to fruition. Despite a preliminary survey in 1901 it was not until 1908 that WA and South Australia, each to their side of the border, undertook a full survey across the desert. Each state ceded the land required for the railway to the Federal Government but three years would pass before any attempt was made to start the project.

That rail transport was traditionally a State function probably contributed significantly to the delay in building the line. Colonial railways were established long before Federation and complex administration was already in place. The Commonwealth was first involved in rail transport when they acquired administration of the Northern Territory in 1911. Along with the Territory came the Palmerston to Pine Creek Railway, a narrow Cape gauge railway of over 500 km built in 1889. It was renamed the North Australia Railway.

During a visit to Australia by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff Lord Kitchener in 1911, he stressed the importance of the Trans Australia line in the defence of the nation to the Federal Parliament and urged them to commence its construction without delay. Hence following the introduction of a bill into Federal Parliament by the Minister for Home Affairs, King O'Malley, a vote for the new Transcontinental Railway was passed on 6th December 1911. Construction of the 1,692 km standard gauge railway, to run from Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta, commenced in 1912. Once construction was underway the new entity to be known as the Commonwealth Railways was created. The Trans Australian line has always been owned and operated by an agency of the Australian (federal) government. There have however been three different authorities over the years.

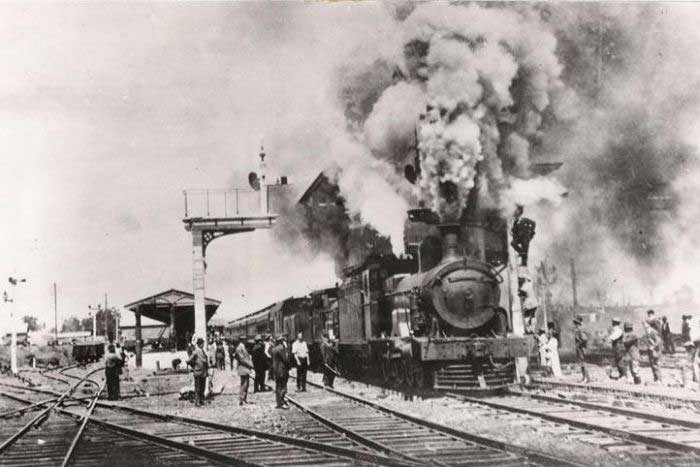

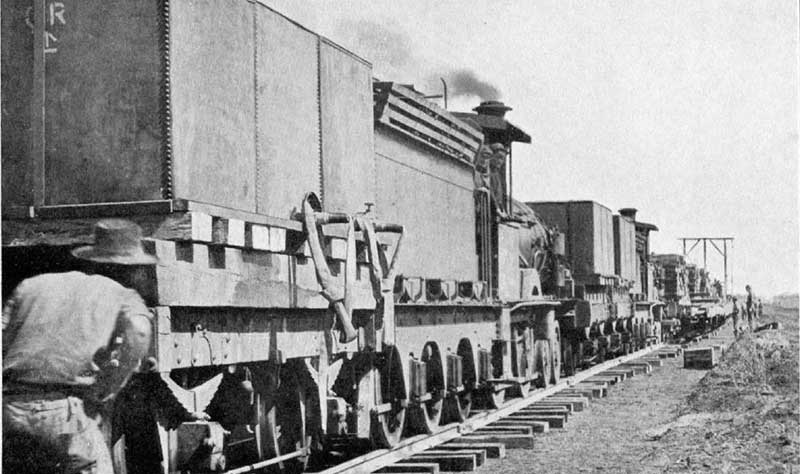

Photo: State Libary of South Australia

Construction of the Trans Australian Railway commenced at each end of the line and the track finally joined about five years later in 1917. The single track line, mainly across the Nullabor plain, included the world's longest straight stretch of railway track (478 km, between Nurina, WA and Watson, SA). Since there were no physical obstacles, not even a single running stream, there were very few technical problems. Because the line crossed 680 km of uninhabited treeless desert, however, there were most certainly significant other challenges - challenges of logistics and the problems with labour, with several thousand men living and working in desert conditions remote from established towns. It was built mainly by men and animal power, supported by 250 camels, a few steam shovels and the first track-laying machine to be used in Australia. Track laying rates of up to four kilometres a day were achieved.

All supplies had to be brought in and housing was moved from camp to camp. Despite problems with labour and supplies due to the 1914-1918 war, construction was completed on 17th October 1917 at a point near Ooldea. One team had worked from the eastern end (starting from Port Augusta) and the other from the western end (Kalgoorlie). These teams had to be equipped not only with the materials to build the railway but also with food, water, accommodation and other supplies for the workers. Despite all tribulations and the great distances, when the two teams met they were less than a metre apart on a north-south line. This made the final joining of the rails very easy. On 22nd October 1917, the first through train left Port Augusta with an official party on board for Kalgoorlie. It should be mentioned that owing to deviation from the original route, the length of the line was reduced from 1,711 km to 1,692 km.

The first eastbound train on then newly-opened Trans-Australian Rail Line. Photo: Rail Heritage WA/State Library of Western Australia)

Four Journeys in One

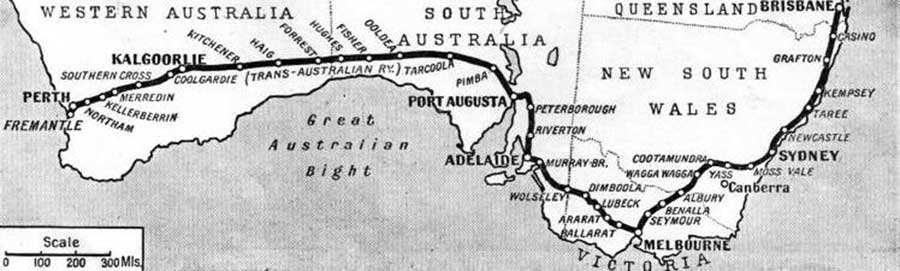

After the Trans-Australian "golden spike" was driven on 17th October 1917, it became technically possible to make the really useful journey across the nation, leaving Melbourne for Adelaide initially in a joint Victorian - South Australian Railways train running on 5ft-3ins (1600 mm) broad gauge track with an engine and crew change at the border station, Serviceton (built specifically built for the purpose), and then travelling north from Adelaide on a different train, though still running on broad gauge track, as far as Terowie in South Australia's mid-north wheat belt, where passengers alighted, crossed the platform, and joined yet another South Australian train, this time running on 3ft-6ins (1067 mm) Cape gauge track (Cape gauge is named after the Cape Province in South Africa which adopted this gauge in 1873).

This next journey took passengers on a circuitous path, eventually joining the old path of the Port Augusta to Alice Springs railway at Quorn in the heart of the Flinders Ranges, then wending its way south-westerly down through the Pichi-Richi pass and across the alluvial flats at the head of Spencer's Gulf into Port Augusta. There passengers once again took themselves and their luggage acoss the platform, joining the Commonwealth Railways standard gauge train, which when leaving Port Augusta climbed up to the Eucolo tablelands, continued on across the Nullarbor Plain (nullarbor literally means "no tree") as far as Kalgoorlie in the Western Australian Goldfields, where passengers once again crossed the platform on to the Cape gauge train which took them the rest of the way into Perth.

Shortly before World War II, a broad gauge main line had been extended northwards from the existing terminus at Redhill into Port Pirie, and the standard gauge had been extended south from Port Augusta to Port Pirie along the western side of the Flinders' Ranges, and one gauge change was thereby eliminated, along with a considerably faster service. However, this now made Port Pirie a three-gauge yard, and some very interesting track formations existed there until the withdrawal of the broad gauge in the late 1980s. Port Pirie Junction station was built by the South Australian Railways in Solomontown, adjacent to one of its widest streets, "Three Chain Road" - 61 metres wide.

By the 1950s, moves were being made to extend the standard gauge line from Kalgoorlie to Perth. November 1962 saw the start of its construction, with the dual-gauge (achieved by using three rails) Avon Valley deviation being opened to Cape-gauge traffic on 14th February 1966, the day that Australia changed to decimal currency. This route replaced the winding and heavily graded route through the Darling Ranges via Glen Forrest and Mundaring, east of Perth. Grain traffic from Merredin commenced in that November, and ore from Koolyanobbing to Kwinana started rolling on the following April. The full standard gauge railway from Kalgoorlie to Forestfield, Kewdale, Kwinana and Fremantle (Leighton) was finally opened to revenue service for freight traffic in November 1968, and to passenger traffic, both local and the trans Australian railway, into new East Perth Terminal, in February 1970.

Tarcoola, South Australia, where the Trans-Australia and Ghan railway lines meet

These days, the time allowed for the journey from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie has been fixed at 37 hours 20 minutes (actual), which gives an average speed of 45.3 km per hour throughout, inclusive of stoppages. Exclusive of stoppages, which aggregate slightly under three hours, the average is about 49 km per hour. In the opposite direction the gross time is 37 hours 30 minutes (actual), which gives an average speed of 45.1 km per hour. Exclusive of stoppages, which aggregate about 3 hours 10 minutes, the average is 49.2 miles per hour. The greatest elevation of the line above sea level is at a point 162 km east of Kalgoorlie, where it is 404 metres. This is a rise of 26 metres above Kalgoorlie. Port Augusta is only 6.4 metres above sea level. With the exception of a short distance of 1 in 80, the ruling grade is 1 in 100.

In The Beginning

On the 1st January, 1911, the Commonwealth Government took over the Northern Territory from the South Australian Government, and at the same time the railways from Darwin to Pine Creek, in the Northern Territory, and from Port Augusta to Oodnadatta, in South Australia, came under its control. Subsequently, the construction of a transcontinental line from Port Augusta, in South Australia, to Kalgoorlie, in Western Australia, was undertaken by the Commonwealth Government, while a line has been constructed in the Federal Territory, connecting Canberra with the New South Wales railway system at Queanbeyan. In 1917 an Act was passed by which all the Commonwealth railways are vested in a Commissioner.

A Federal Act passed in 1907 provided for the expenditure of a sum of £20,000 for a preliminary survey of a railway line connecting Western Australia with the eastern States. This survey was commenced in 1908, and was completed in March, 1909. The route via Tarcoola was, for several reasons, chosen in preference to that via Gawler Range and Fowler's Bay. The estimated cost of construction and equipment of the line on the basis of a 4-ft. 8 1/2-in. (1,435 mm) standard gauge, from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in the Western Australian goldfields, a distance of 1,710 km, was £4,045,000. In September, 1911, a Bill was introduced into the Commonwealth Parliament to authorise the construction of the line, and it became law in December following.

In South Australia an Act was passed enabling the Common wealth to acquire lands for the railway in South Australia not exceeding one-eighth of a mile wide on either side of the line, but no town lands are to be included at any time. In Western Australia, an Act was also passed by which all necessary lands are to be granted to the Commonwealth for railway purposes. A Railway Construction Department was created by the Federal Government to carry out the work, which was commenced at Port Augusta in September, 1912. On 12th September the ceremony of cutting the first sod was performed at Port Augusta by the Governor-General, Lord Denman, in the presence of a representative gathering, and on the 12th February, 1913, a like ceremony was performed at Kalgoorlie by the Prime Minister of the Commonwealth (the Right Hon. Andrew Fisher), and the line was thus commenced at both ends.

The Route

The country traversed by the new line was roughly divided into four sections from Kalgoorlie eastward. The first section comprises the granite plateau extending for 269 km out from Kalgoorlie. Much of the country on this section is fairly well timbered with salmon gums and other eucalypts, running up to 16 metres in height. Kurrajong and sandalwood are also fairly abundant. Throughout there is a luxuriant growth of wild flowers.

The second section is "the limestone plain," which runs for 720 km to the east from the edge of the granite country. In this section the eucalypts suddenly disappear, and are not seen again until the mallee gums of the bolder sandhills on the eastern edge of the plain are reached. The open plain comes into view 330 km out, and thence forward the only signs of growth to be observed are the saltbush and blue bush.

About 470 km out the line runs on to the Nullarbor Plain. One feature of this part of the line should be mentioned, viz., that it runs straight for no less than 478 km. This is believed to be the longest section of straight-line railway in the world. Near Loongana, 540 km out, caves are situated, the principal of which is Lynch's.

The South Australian border is reached at a point 730 km out, a small stone cairn marking the boundary. At 975 km trees are again met with, but they are small and do not grow more than ten to twelve feet high. The limestone plain is left at about 1,000 km out.

The third section is the belt of sandhills on the eastern edge of the limestone region, through which the line runs for about 80 km. In a state of nature, there are no shifting sandhills about this part of the line, as there is a fairly thick growth of small trees, Mallee gums and others, but when the surface is cleared, the soil is easily removed by the wind, and the bigger cuttings for the line have had to be faced with stone.

The fourth section comprises the stretch of country extending for nearly 640 km from the eastern edge of the sandhills to Port Augusta. For about 160 km the line runs over red soil plains and undulating country, which give promise of pastoral and possibly agricultural uses. At Wynbring, 1,175 km out, the granite again comes to the surface. One of the most important places on this section is Tarcoola, at which gold mining has been carried on for some time past. East of Tarcoola the Lake country is entered. The lakes in this district are merely vast shallow pans, which are beds of salt in dry seasons and contain water only after rains. It may be mentioned that the line does not cross a single permanent stream of water at any part of its length of 1,692 km.

The line originally passed through Pichi Richi Pass in South Australia's Flinders Ranges on a section of track now used by the Pichi Richi Tourist Railway, and through Quorn on a section of track used for the original Ghan railway from Adelaide to Oodnadatta, then Alice Springs. Quorn was a vital railway junction, especially during World War II when military, coal and other traffic placed sizeable demands on the railway. Washaways in the north and the incapacity of the railway to handle expanding traffic saw a new section of line constructed from Stirling North to Brachina in 1957. The Pichi Richi Railway was closed to regular traffic at that time.

Construction

At first preparatory work at each end of the line had to be done, and it was not until March 1913, that any platelaying had been carried out. By 30th June, 1913, 5.6 km of line on the 3-ft. 6-in (1067 mm) narrow gauge, and 1.6 km on the standard gauge, had been laid in the depot at Kalgoorlie, the corresponding lengths at Port Augusta being 7.3 km and. 4 km respectively. Platelaying on the main line was commenced on the eastern division on April, 1913, and on the western division in May, 1913.

Between 1st September 1913, and 17th October 1917, the date on which the eastern and western divisions met at just over 1,000 km ex Kalgoorlie, a total of 1,670 km was completed. Including Sundays and holidays this gave an average of 1.1 km of line per day; omitting Sundays the average was 1.3 km of line per day. The line itself consisted of rails weighing 36 kg to the metre and is a single line throughout, with the exception of the lines at the terminal stations. The rails varied in length, some being 10 metres and others 13.7 metres, the latter having been adopted to reduce the number of rail joints. The sleepers were at first 2.74 metres, 254 mm wide by 127 mm in depth. Subsequently they were standardised at 2.59 metres long, 228 mm wide and 127 mm in depth, thus effecting a material saving in timber.

At Port Augusta it was necessary to erect a new station on a fresh site, the original station site being entirely unsuitable for the purpose of the new line. The station buildings were constructed so as to accommodate the officials of the various departments connected with the railway. Engineering and other shops were erected and operated to carry out the erection and repair of the locomotives and other rolling stock. It was the intention of the Railway Department to undertake the construction of all the rolling stock required for its lines when the conditions for such construction become favourable. Provision were also made at Kalgoorlie for the repairs to rolling stock and other railway material. The intermediate stations on the line had no platforms, the passenger rolling stock being designed so that passengers can get on or off the train without any difficulty at the rail level.

Borings for water were made at many points along the line. In certain cases the daily supply from some of the bores was small, and the water obtained not satisfactory for locomotive purposes. In other cases the results were more satisfactory. On one 542 km section of the line, there was not any local water to be obtained, and all the water required for locomotives, machinery, men, and animals on that stage had to be conveyed by rail. Owing to the natural difficulties on the route, the Railway Department had to cater and provide for the staff entirely, such operations necessarily entailing a large amount of extra work other than that of the actual construction of the line.

Maintaining the Line

As the whole locomotive power of the initial railway was steam-drive, and the country through which its passed was arid, the most important problem was water supply. On the Nullabor Plain, surface storage of water was such that, in normal times, it was common for all reservoirs to be exhausted at least for part of each year, and recourse to underground supplies was necessary. On no other railway in the world were the supplies of underground water more deleterious to locomotive boilers than those on the Trans-Australian Railway. On one stretch of more than 400 miles, there is no permanent source of supply. To facilitate the maintenance of the line, it was decided to establish small settlements of six houses per siding and 30 km apart along the most isolated sections of the line on the Nullabor Plain.

Sidings on the Nullarbor

A number of sidings were built to allow trains coming from the opposite direction to pass each other on the single-track line. The sidings were named after early Australian Prime Ministers. The three roomed corrugated iron houses at these sidings were T-shaped, with each room being linked by open latticed-walled corridors. All cooking was done on a wood stove. Without refrigeration food could not be kept, and meat especially had to be cooked as soon as it had been purchased from the Tea and Sugar Train. A 'pit' or 'dry' toilet (a long drop) at the bottom of the yard, and tin (galvanised) tubs and baths were all that served as conveniences. The rain water tank was filled from the catchment area provided by the roof of the house when it rained. This precious water was for drinking only. Water for their domestic purposes came from tanks filled with water carried from Port Augusta in water wagons included with the weekly train. Water was carried to the homes in buckets.

Cook siding

Cook had a school where students attended normal lessons. Students - known as line kids - at places such as Barton were able to enrol in the Open Access College at Marden through which they could do their correspondence lessons, or they could enrol in the Pt Augusta School of the Air. Students enrolled in these colleges had direct access to teachers through a telephone bridge. Their written work was railed in to their teachers who would mark it.

The Tea and Sugar train

The Tea and Sugar Train

In 1915 it was proposed that a supply train provide food and water for the navvies (railway worker) maintaining the East-West link. With the completion of the line, the supply train became the lifeline of the fettler (track layer or repairer) communities, bringing them food, water, clothing, household items, letters and news of the rest of the world. It became known as the Tea and Sugar train. A similar supply train referred to as the Slow Mixed, later serviced the communities along the northern line to Oodnadatta.

World War II POW Camps

The Trans Australian Railway would fulfill Lord Kitchener's prediction of its importance for Australia's defence during World War II. During the years 1942-44 the east-west railway line was generally unavailable for any non-military use, due to its vital role in the transport of troops and equipment. To meet the rapidly growing service during the war years, a large programme of expansion of water supplied was undertaken. Reservoirs were built and enlarged, bores were sunk, water treatment and pumping plants were installed, tank storage was increased.

POW camp, Nurina, c.1950s

Located 490 km east of Kalgoorlie on the WA side of the border, Nurina was the site of a World war II Prisoner of War camp. It was officially known as the Cook POW Labour Camp No. 3 POW Labour Detachment. In April 1942, approximately 300 Italian prisoners of war were put to work on the Trans Australian Railway to expedite sleeper renewals. These men were placed at six locations where camps had been prepared for them. A Military camp was established at Cook for the headquarters staff. During the twenty months the prisoners of war were engaged on this line, the highest effective strength was 240. Most of the POWs were repatriated to their homelands by the middle of 1947 although some were given permission to remain in Australia. Very little remains today of the camp.

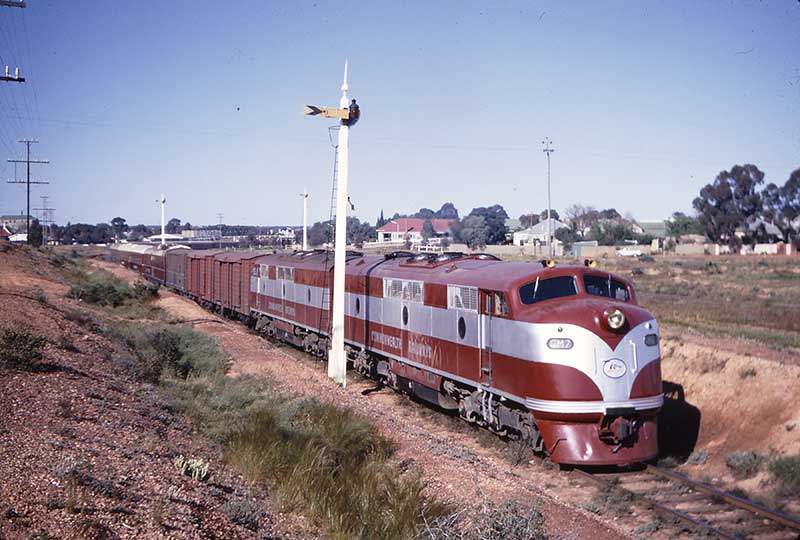

Eastbound Trans Australian Express GM 7 GM 1 leaving Kalgoorlie, WA, 18 September 1967. Photo: Weston Langford

Steam to Diesel

The switch from steam to diesel powered locomotives began in 1951 with the introduction of the maroon and silver GM Class Diesel Locamotive. This improved conditions for the train crews considerably. Diesels locomotives not only eliminated the need to shovel coal into the hot furnaces of the locomotives during the sweltering summers on the Nullarbor, they shortened the time taken to serve the remaining camps, although the distance was still the same. Education for children living at these settlements on the line was still based on lessons from the correspondence school, but modern technology provided a direct link between students and teacher(s) by means of the DUCT system (a telecommunications link). Modern, faster diesel travel now permitted the occasional visit from a teacher. Larger centres had schools which enabled some students to experience school life in much the same way as their urban cousins.

In the 1980's railway engineering advanced rapidly and with some urgency adopted a range of low maintenance materials that essentially eliminated the need for local maintenance gangs. Most notably the use of highly durable concrete sleepers was adopted, and together with the ability of modern diesel locomotives to travel very long distances without refuelling, the staff along the line began to dwindle.

One by one, settlements along the Trans-Australia line were abandoned and the families from these communities were settled elsewhere. But not all the towns were 'dead men's camps' and the Tea and Sugar Train still supplied isolated communities along the railway line out on the Nullarbor for a number of years. The last trip was made on 30th August 1996 ending a colourful chapter in railway operations in Australia. Today, the only place with permanent railway staff is Cook, where one couple remains to manage the facilities for locomotive refuelling and for the 'watering' of the weekly (in both directions) Indian-Pacific service.

The Indian Pacific

Today's trans-Australia railway service - The Indian Pacific - which travels from the west coast to east coast on a 3-day, 4,352 km trek across Australia, is billed as one of the world's great train journeys. The three day trip (if you do it all in one go) takes you through just about every kind of terrain you're likely to find on the Australian continent, giving travellers a true indication of how vast Australia really is.

Design by W3layouts